Week 1

We are the most sedentary society that’s ever existed on Earth. Yet, our bodies are physically and fundamentally designed to move. Chronic disease starts to set in when we cease to move, a direct result of the establishment of our genome from the hunter-gatherer days.

Even a small amount of activity provides enormous benefits. For someone who is chronically sedentary, just 20 minutes of movement can provide almost immediate improvements: a reduced risk for heart disease, diabetes, cancer, and dementia.

How is that possible, though? How can something so simple—just 20 minutes into a workout—create such enormous impact?

What the Science Says

Surprisingly, even in this day and age, we still know very little about all of the complex, seemingly countless biological processes that occur inside our bodies when we move.

And yet, there is no disputing it: a walk a day can lead to not only longer, but also healthier lives years from now.

Understanding exactly how exercise impacts these biological systems is paramount: it can give us a much deeper, more profound perspective that can help us understand how movement works in our favor.

In a recent study, researchers attempted to uncover every single molecule in the body that changes during exercise: a seemingly impossible task, given that there are hundreds of thousands of molecules shifting at any given moment. Researchers collected blood samples from their volunteers prior to and immediately following a treadmill endurance test.

The results were mind-boggling.

Of the 17,662 molecules measured, 9,815 of them changed due to exercise. Some molecular levels went up, while others went down; some changed immediately following the workout, while others fluctuated hours later.

In many blood samples, the researchers found that molecular markers of inflammation, oxidative stress, and tissue repair spiked just after participants got off the treadmill, as their bodies began to normalize. They also found that in cases of insulin resistance (IR), there were smaller increases in molecules that help regulate blood sugar and higher levels of molecules related to inflammation.

In another study, researchers again focused on certain blood molecules during a bout of hard exercise. Volunteers’ blood was taken prior to getting on a stationary bicycle; participants then rode until exhausted. Immediately after they got off the bike, their blood was collected again. In both blood samples, researchers focused specifically on molecules related to metabolism, known as metabolites: molecules impacting blood sugar, insulin, cholesterol, and fat burning levels, as well as other metabolic fueling mechanisms.

Of the hundreds of metabolites examined, researchers found the molecular levels were in a (mostly) constant fluctuation. With barely 10 minutes of exercise, the data pointed to enormous molecular shifts happening on the inside.

The researchers found that the exercise process was spurring hundreds of biochemical reactions, both immediately and long after completing a workout.

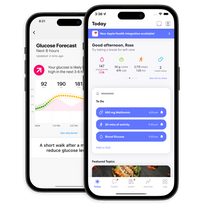

Blood Sugar Spikes Caused By Exercise

Interestingly, blood sugar tends to rise during and even after intense workouts (high-intensity interval training, or HIIT) in just about everyone, including people without diabetes or prediabetes.

It’s currently believed that these high-intensity bouts of exercise stimulate certain hormones like epinephrine, which prompt an excessive amount of glucose production in the liver. The muscles, which use glucose for fuel, only need about half as much as is being produced, resulting in an oversupply of glucose in the blood.

You may be thinking: an increase of glucose in the blood surely is never a good thing. But—for those not dependent on exogenous insulin—these elevated glucose levels will signal a need for insulin; insulin is then produced by the pancreas, muscles absorb the excess glucose, and blood sugars return to baseline.

What’s more, those bursts of high-intensity training can alter insulin sensitivity in a matter of days; heightened insulin sensitivity levels can mean better, more in-range blood sugars.

While it may seem counterintuitive, that initial blood sugar spike (which is essentially the body getting rid of too much of its own glucose stores) leads to better overall blood sugars and, ultimately, metabolic health.

What Does It Mean?

Within minutes of beginning to move, we can alter our entire molecular profile.

While the exact mechanics aren’t fully understood yet, there is no doubt that something miraculous happens inside the body when we move. When we choose activity—in whatever capacity—we are turning on a molecular symphony. And the more often we ignite that symphony, the more we strengthen those molecules, enhancing every molecular process along the way.

In turn, the better the outcome we create for our lifespan.