Too often, Mary Elizabeth Adams has found herself consumed by frustration after an intense workout. Despite being told by countless doctors that exercise will help her manage her type 1 diabetes by lowering her blood sugar, she’d routinely see her glucose spike during a workout session and struggle to understand why. It wasn’t until Adams started digging deeper into the data provided by her continuous glucose monitor (CGM) that she discovered why some forms of exercise were making her blood sugar spike higher than others.

“I cannot tell you how many times I cried in the locker room at the gym because I was like, ‘Why is this happening to me? What am I doing wrong?’” shares Adams. “And I was afraid to take insulin in response because, well, what if I bottomed out?”

What CGMs Can Do for People with Diabetes

CGMs automatically track blood sugar throughout the day and night via a tiny sensor inserted under the skin (usually on the stomach or arm) that measures the amount of glucose in the fluid between cells. That data is sent to your smartphone (or another connected reader) in real time to give you a clear picture of the cause-and-effect relationship between your blood sugar and your nutrition, exercise, medication, and other lifestyle choices. Some CGMs are even connected to an insulin pump that can automatically deliver the right amount of insulin based on your blood sugar readings.

Research shows that blood sugar readings from CGMs tend to be just as accurate as readings from glucose meters (e.g., the method that involves finger-pricking and test strips to see your current glucose level). That said, though,it’s never a bad idea to double-check your CGM data with your glucose meter to get an even fuller picture of your health, including not only real-time data, but also long-term forecasts and insight about what you can do to influence your health journey moving forward.

Still, there’s no denying that CGMs offer more convenience than glucose meters. “Instead of having to prick your finger, get a drop of blood, use a glucose meter, and get those readings multiple times a day, CGMs give you dozens and dozens of data points in the background,” Casey Means, M.D., a Stanford-trained physician and associate editor of the International Journal of Disease Reversal and Prevention, explained in an episode of the Diet Doctor Podcast. “The beauty of this is that, as opposed to just getting a single snapshot of what’s happening to your glucose levels in response to dietary and lifestyle choices, you’re seeing the dynamic action of the body, and you’re getting much more granularity into your overall metabolic health.”

For example, when Adams realized that some of her workouts were raising instead of lowering her blood sugar, she looked more closely at her CGM data to figure out what was going on. Thanks to the combination of granular and big-picture perspectives provided by her CGM, she discovered that a specific combination of high-intensity cardio and strength training with hand weights was causing her blood sugar to spike, while other forms of exercise, such as fast-paced walking, didn’t spike her glucose levels (presumably because of the adrenaline rush associated with intense exercise, and the subsequent production of stress hormones that can lead to a rise in blood sugar).

Essentially, CGMs can help someone with diabetes (or even prediabetes) parse out the nuances of their blood sugar management beyond just cutting carbs and keeping an eye on their weight, says Erin Decker, a registered dietitian (RD) and certified diabetes care and education specialist (CDCES)

“What affects one person’s glucose won’t necessarily be the same for someone else,” explains Decker. “Using a CGM allows you to see exactly how various foods and activities affect you personally.”

What CGMs Can Do for *Everyone*

CGMs are most commonly prescribed to people who’ve already been diagnosed with type 1 diabetes or, in some cases, type 2 diabetes (typically only for those who are using insulin).

However, more and more experts are exploring the use of CGMs in broader populations—specifically, people who don’t have diabetes.

At the 14th International Conference on Advanced Technologies & Treatments for Diabetes (ATTD 2021), for example, Spencer Frank, Ph.D., an algorithm engineer at Dexcom, presented research comparing the use of the Dexcom G6 (the company’s latest-generation CGM) and the oral glucose tolerance test (OGTT, the “gold standard” blood test for diagnosing prediabetes and diabetes) as tools for diagnosing diabetes. The findings suggested that just 10 days of CGM data can be used to diagnose diabetes with similar accuracy and performance, yet more convenience, compared to the OGTT.

Now, imagine if you had convenient access to those details about your blood sugar long before you reached diabetic, or even prediabetic, levels. Considering that conditions such as type 2 diabetes typically exist on a spectrum, “you’re likely progressing along this spectrum of metabolic dysfunction over the course of years, if not decades, from repeated choices and exposures that lead you toward insulin resistance,” Dr. Means explained on the Diet Doctor Podcast. But if you have more granular information about your blood sugar levels over time, that means “you can tailor your diet and lifestyle to minimize glucose spikes that ultimately push us down the path of insulin resistance and overt metabolic dysfunction,” said Dr. Means.

In other words, even though CGMs are traditionally used to reactively manage or treat diabetes, experts such as Dr. Means argue that the tool can (and should) be used to preventatively lower the risk of developing diabetes and other metabolic conditions in the first place, by familiarizing us with the relationship between our blood sugar and our daily lifestyle choices.

“CGMs allow for personalized goal-setting, lifestyle changes, and the ability to see immediate impacts on your health markers,” explains Decker. “That can be very powerful motivation.”

The Barriers to Broader CGM Access

Cost and eligibility are two of the biggest barriers to CGM access. While Medicare, for example, covers CGMs for qualifying individuals, the qualification requirements are often called “restrictive” and “unjustified.” In many cases, you’ll only qualify for CGM coverage if you have type 1 (not type 2) diabetes and can prove that you routinely use at least four finger-stick blood sugar tests per day (even though Medicare only covers about three test strips per day for those using insulin). As for commercial insurance providers and state Medicaid programs, CGM coverage can vary widely depending on your circumstances. Without insurance, it’s estimated that CGMs can cost at least $100 per month, if not more.

There’s also the issue of a lack of data to support broader CGM access. As of now, there are very few studies assessing CGM use in people without diabetes, and the research that is out there largely includes small sample sizes and early-generation CGM devices that aren’t as accurate as the tools currently on the market.

Without that data, “we don’t have norms for how high or low the occasional glucose goes in healthy people,” Daniel Einhorn, M.D., clinical professor of medicine at the University of California, San Diego, told Endocrine Today. “We have no comprehensive studies to account for age, sex, race, or other variables, so it’s not clear what CGM results will be actionable. That said, I would love to see research into what ‘normal’ CGM looks like and would support it.”

As Peter Attia, M.D., a physician who specializes in the science of longevity, recently wrote, the only way to get that data is to start using CGMs to track blood sugars in healthy populations. Yes, methods such as A1C tests, OGTTs, and fasting glucose tests are considered the standard means of assessing blood sugar levels and potentially diagnosing diabetes. However, “just because someone’s fasting glucose or HbA1C levels are considered normal doesn’t rule out the possibility that they have high glucose variability, which are large oscillations in blood glucose throughout the day, including episodes of hyperglycemia and hypoglycemia,” explained Dr. Attia. High glucose variability (whether accompanied or unaccompanied by a diabetes diagnosis) has been linked to a number of long-term health issues, including an increased risk of heart conditions, dementia, and death from any cause. But, as Dr. Attia wrote, fasting glucose and A1C tests don’t necessarily show us the extent of someone’s glucose variability and whether their levels are truly “normal.”

CGMs, on the other hand, can provide some clarity. For example, a 2018 study published in PLOS Biology showed that, in 57 people without diabetes who wore CGMs for up to four weeks, severe glucose variability was present in 25% of participants. What’s more, results showed that, among those with high glucose variability, blood sugars reached prediabetic or diabetic levels 15% and 2% of the time, respectively.

While the study authors echoed the need for larger and more long-term studies to confirm the benefits of using CGMs in people without diabetes, they also noted that, if CGMs become more accessible and affordable, “using this metric of glycemic variability may enable earlier and possibly expanded detection of individuals at risk for type 2 diabetes and cardiovascular disease.”

The Future of CGM Access

Again, until we have more clinical trials on the subject, it’s hard to estimate just how useful CGMs might be in a broader population outside of just people with diabetes.

But, as experts in the space have noted, the only way to gauge the effectiveness of CGMs in these general populations is to give these folks access to not only the technology, but also personalized coaching services that can help them truly understand, interpret, and act upon their health data.

For Mary Elizabeth Adams, understanding her CGM data was a “life-changing” experience. “It does take awhile to understand the data,” she admits. “But it all comes down to how much you’re willing to engage with the technology. The more you put into it, the more you get out of it. The more you look at your own data, the more you start to see certain patterns. And from those patterns, you’re able to make your own health decisions, as opposed to waiting months and months until you see your doctor next.”

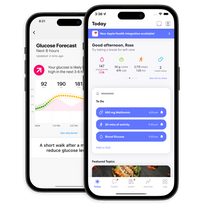

On the bright side, more and more continuous health-screening tools like continuous glucose monitors are coming to the market. Keep an eye out for more details on One Drop’s multi-analyte biosensor, which will make continuous health sensing more accessible and affordable to people with living type 1 diabetes, type 2 diabetes, and other chronic conditions.

This article has been clinically reviewed by Jamillah Hoy-Rosas, MPH, RDN, CDCES, and VP of clinical operations at One Drop.