When Sarah Leonard began seeing changes in her body after starting estrogen therapy at age 16, she says she felt “overjoyed” and “more like herself” than ever before. Six years later, she credits gender-affirming hormone therapy (GAHT) for “drastically” improving her body image.

“I’m able to be out publicly and love the way I look and feel without having to put up a facade,” she shares.

For Nathan Blue, starting testosterone injections at age 27 had both ups and downs. He describes the first few months as an “intense” time marked by mood swings and hunger pains (both common side effects of testosterone injections). But, after adjusting his dose, Blue says his “mental and emotional well-being is the best it’s ever been.”

“Even with the physical ups and downs, I know it’s right for me,” he adds.

There’s no question that GAHT—which involves taking hormones like testosterone and estrogen so you can acquire secondary sex characteristics that are more aligned with your gender identity—can improve mental health and self-esteem. But, like any other medical procedure, it can also come with side effects and, depending on your health background, some potential risks down the road. Namely, the risk of high blood pressure could be a concern when taking certain forms of GAHT, according to new research published in Hypertension, a journal of the American Heart Association (AHA).

The Link Between Hormone Therapy and Hypertension

For the study, researchers monitored the blood pressure of 470 transgender and gender-diverse adults (247 of whom were taking transfeminine hormone therapy, and 223 of whom were using transmasculine hormones) who began GAHT at a medical center in Washington, D.C. between 2007 and 2015. To establish a baseline, researchers measured each person’s blood pressure before they began GAHT and continued to take regular readings for up to about five years.

According to the study, researchers found that, within the first two to four months of GAHT, the treatment was associated with lower blood pressure among transfeminine participants, and higher blood pressure in the transmasculine group. These trends continued “throughout the duration of follow-up,” the study authors wrote.

Another key finding: Among transfeminine people in the study, the prevalence of stage 2 hypertension—the stage when your doctor will likely suggest both lifestyle changes and blood pressure medication to help keep your numbers stable—dropped from 19% at baseline to 10% within the first two to four months of hormone therapy. That number eventually fell to 8% at 11 to 21 months post-GAHT, according to the results.

Among the transmasculine group, however, the rate of stage 2 hypertension was similar across time. And yet, researchers found that the prevalence of stage 1 hypertension—which usually only requires lifestyle changes to manage, and potentially medication, depending on your overall risk of heart disease or stroke—among transmasculine participants was higher after 11 months of GAHT.

TL;DR: Based on these findings, transfeminine hormone therapy seems to be associated with lower blood pressure, while transmasculine GAHT appears to be linked to higher blood pressure.

How Poor Data Leads to a Lack of Understanding

Despite the findings in the Hypertension study, the general relationship between GAHT and blood pressure is more complicated than it seems.

For one thing, the available research on the subject has several shortcomings (think: small sample sizes, short follow-up periods, lack of standardization in hormone-therapy delivery), according to a 2020 review published in the Journal of Hypertension—all of which lead to inconsistent outcomes. While the 2021 Hypertension study suggests a link between transmasculine hormone therapy and high blood pressure, the 2020 review notes that, of the 14 studies included in its analysis, most actually didn’t show a significant change in blood pressure among transgender men taking GAHT. Meanwhile, transgender women taking hormone therapy “demonstrated both increases and decreases” in blood pressure across the studies included in the review, the authors wrote. Given the variance in results, none of these findings seem to offer any slam-dunk conclusions.

Even though the 2021 Hypertension study authors described their research as “the largest and longest observational study to date” on the subject, they also admitted that their research is limited by a few factors, including a lack of a control group and inconsistency in protocols for blood pressure monitoring. Plus, the hormone therapies represented in the research were limited to testosterone injections among transmasculine participants, and oral estradiol (a form of estrogen) and spironolactone (a diuretic that blocks the body’s production of androgens, a male hormone) in the transfeminine group. That means the results can’t be generalized to people who receive different forms of hormone therapy, such as estrogen injections or testosterone patches, according to the paper.

So, based on the studies currently out there, it’s hard to draw any clear-cut connections between high blood pressure and GAHT. “There are many important gaps in our knowledge about the effects of hormone therapy for transgender people,” Michael S. Irwig, MD, director of transgender medicine at Beth Israel Deaconess Medical Center and senior study author of the 2021 Hypertension study, confirmed in in a press release.

Understanding What We *Do* Know About Transgender Heart Health

Blood pressure aside, we know there are significant disparities in overall health between LGBTQIA+ and straight, cisgender people. The key, then, is to figure out what’s causing those disparities. In the context of heart health among transgender people, is hormone therapy really a deciding factor, or are there other circumstances at play?

Joshua D. Safer, MD, FACP, FACE, executive director of the Center for Transgender Medicine and Surgery at Mount Sinai Health System, says discrimination likely plays a big role. “Transgender people suffer from lack of access to healthcare and from being the target of much negative commentary, including from some people in political leadership positions,” he explains. “The degree to which those stressors explain health concerns among transgender people has not been measured well.”

However, he continues, since research has yet to show a strong, consistent link between GAHT and heart health risk factors (such as high blood pressure), “it seems logical to consider alternative explanations.”

That said, there is the possibility that some forms of estrogen therapy for transgender women can come with an increased risk of blood clots and, therefore, a higher risk of stroke, adds Dr. Safer. Still, plenty of research shows that the same can be said for birth control pills and blood clot risk among cisgender people. Plus, continues Dr. Safer, “it’s notable that among cisgender women receiving post-menopausal hormone treatment, those that receive progestins [a form of progesterone, a hormone involved in menstruation and pregnancy] are the ones with the more concerning cardiac disease profiles,” he explains. “And because progestins are included in treatment for people with uteruses, transgender women aren’t classically treated with progestins.”

So, if not GAHT, what else could be playing a role in heart health issues among transgender communities? Aside from possible discrimination at the doctor’s office, a 2020 statement from the AHA notes that transgender adults, on average, report lower physical activity levels than their cisgender counterparts. And, interestingly enough, the statement says that gender-affirming care (such as hormone therapy) can actually promote heart health by helping trans people feel more comfortable in their bodies and, as a result, more motivated to stay active.

What You Really Need to Know About Hormone Therapy and High Blood Pressure

As with nearly any other medical treatment, undergoing GAHT means keeping an eye out for possible side effects and health complications—especially over time. Case in point: When it comes to high blood pressure and GAHT, “the larger studies that show change in blood pressure mostly do so over time,” explains Dr. Safer, “which may just mean they’re measuring the expected rise in blood pressure with aging.”

In other words, it’s a good idea for everyone, regardless of gender identity, to keep tabs on their blood pressure as they get older.

For Nathan Blue—who’s been receiving testosterone injections for nearly a year now—that means being more proactive when it comes to doctor’s visits. “I began hormone therapy during quarantine, so my communication with my doctor has been extremely limited,” he explains, adding that he wants to prioritize a check-up soon, especially now that he recently started seeing a new doctor. “I’ve been doing blood tests to check on my [hormone] levels, but I want to make sure I’m staying on top of my blood pressure, too,” he shares.

Sarah Leonard, who’s been using hormone therapy for several years, says she and her doctors have scheduled regular check-ups, screenings, and blood-work panels over time to track any changes in her health, including her heart. In the absence of any family history or other risk factors that could predispose her to heart health issues, Leonard says she and her doctors “aren’t worried about those side effects.”

“It’s not something that ever dissuaded me,” she adds. “It’s simply an extra thing on my checklist for doctor’s visits.”

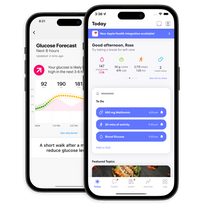

If you need help creating a checklist for your own doctor’s visits, be sure to download the One Drop app and connect with one of our coaches, who can help you take ownership of your self-care outside the doctor’s office, no matter what your health history or wellness goals may look like. And, for those looking to track their blood pressure, One Drop’s new blood pressure insights can help you spot trends, receive alerts for hypertensive crises, and proactively reduce your risk of complications.