Read time: 10 minutes

- We all need insulin to survive. But, if you live with diabetes, your body doesn’t make or use insulin the way it’s supposed to, meaning you might need insulin therapy.

- There are multiple types of insulin, not to mention a few different ways to administer it, and it all depends on your unique health background.

- Taking insulin can come with a big learning curve, but with your One Drop coach and the rest of your healthcare team there to support you, nothing is impossible.

Regardless of whether you live with diabetes, everyone needs insulin to survive. But, if you do live with diabetes, your body doesn’t make or use insulin as effectively as those who don’t live with the condition, meaning you might have to use insulin replacement therapy to manage your health. So, what exactly is insulin, and how do you navigate insulin therapy when you live with diabetes? Find out all you need to know in this complete beginner’s guide to insulin.

What Is Insulin? And When Do You Need Insulin to Manage Diabetes?

“Insulin is a hormone made by the pancreas that helps your body use glucose (sugar) for energy,” explains One Drop coach, Lindsay Vettleson, a registered dietitian/nutritionist (RDN), certified diabetes care and education specialist (CDCES), and certified personal trainer (CPT).

When your body can’t make enough insulin or use it effectively enough (a main characteristic of diabetes), continues Vettleson, it can be given by injection, inhalation, or through an insulin pump instead.

But do you always need insulin if you live with diabetes? Well, it depends.

“The difference between type 1 and type 2 diabetes is what’s going on in the beta cells of the pancreas,” says One Drop coach, Lisa Goldoor, CDCES and registered nurse (RN). “Type 1 diabetes is an autoimmune condition in which the beta cells are destroyed by the body and therefore are unable to produce insulin—meaning those living with type 1 diabetes need to take insulin in order to survive.”

Type 2 diabetes, on the other hand, is a metabolic (rather than autoimmune) condition in which the beta cells can and do produce insulin, “but the body isn’t able to use it or regulate it properly,” continues Goldoor. “People with type 2 diabetes may need to use insulin, but they also have other options, including medications that help them use their own insulin more effectively, as well as lifestyle modifications, such as eating fewer carbs per meal, exercising, and losing weight.”

The decision to use insulin to manage type 2 diabetes is one that should be made between you and your doctor with consideration for multiple details, notes Goldoor, including your current blood sugar levels, medication cost and affordability, and your ability and willingness to engage in insulin therapy (read: are you comfortable with regularly injecting yourself with needles or wearing a medical device on your body?), among other circumstances.

In some cases, adds Goldoor, insulin may also be recommended for those living with gestational diabetes, a type of diabetes that can develop during pregnancy when a hormone made by the placenta interferes with the body’s ability to use and regulate insulin for yourself and your developing baby. Again, though, your best bet is to have an open dialogue with your doctor about your insulin needs and options.

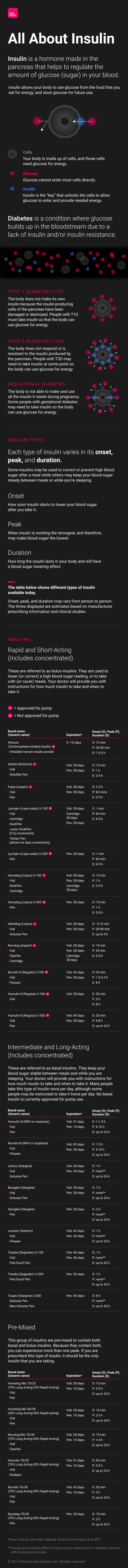

Breaking Down the Different Types of Insulin

The type of insulin you use to manage diabetes will depend on multiple factors, from personal preference and insurance coverage (or lack thereof) to current blood sugar levels.

Generally speaking, the categories of insulin are broken down by duration, explains Goldoor. Faster-acting insulins (a.k.a. bolus) absorb quickly from your fat tissue into your bloodstream to help manage high blood sugar and are typically used at mealtime to manage food intake (particularly carbohydrates). Longer-acting insulins (a.k.a. basal), on the other hand, absorb more slowly into your bloodstream and are used to manage what Goldoor calls “normal body processes” that can sometimes naturally increase your blood sugar, such as your metabolism and the release of certain hormones.

“In type 1 diabetes, both faster-acting and longer-acting insulins are used in combination to mimic how the pancreas functions,” explains Goldoor. Administering a combination of the two can either be done with two different injections or in a combined medication (think: a 70/30, 50/50, or 75/25 split of both types of insulin in the same syringe).

“These combinations can help to reduce the number of overall insulin injections,” notes One Drop coach, Alex, RDN, CDCES. “However, it’s critical to match your meals with the timing of a combination dose of insulin, whereas there can be more flexibility in the timing of meals when you’re taking only basal or only bolus insulin.”

In type 2 diabetes, however, Goldoor says you might only need one type of insulin or the other, or potentially both, depending on when your blood sugar levels tend to be highest.

Having trouble remembering the difference between bolus and basal? “A helpful tip is to think of bolus (faster-acting insulin) as a ‘bowl’ of food,” suggests Alex. “Most people will take their mealtime insulin (a.k.a. bolus) with food or as a way to manage high blood sugar levels.”

For basal, Alex recommends thinking of this type of insulin as “long” or as a “baseline,” since it keeps your blood sugar levels between meals and while you’re sleeping (meaning it’s working in the background).

There’s also intermediate-acting insulin, which absorbs into your bloodstream more slowly than fast-acting (bolus) insulin, but not quite as slow as long-acting (bolus) insulin. Still, since the effects come on more slowly and last longer, that means intermediate-acting insulin can also be an option for managing blood sugar overnight, between meals, or during other fasting periods.

For an even deeper dive into the different types of insulin, take a look at our insulin infographic below.

Administering Insulin

According to the Juvenile Diabetes Research Foundation (JDRF), there are three main methods for administering insulin: injections, inhalers, and insulin pumps.

Injections, which can be done via syringes or pen needles, are usually done at regularly scheduled times throughout the day, though the exact number of doses and timing of those doses will largely vary from person to person. The shots are subcutaneous, which means you’re injecting the insulin into the tissue layer between the skin and muscle with a short, thin needle (whereas with a flu shot, for example, the injection is given in your arm muscle with a bigger needle).

As for inhalation, Afrezza is an FDA-approved, quick-acting inhaled insulin that’s meant to be used for mealtime (meaning you inhale immediately before eating). While many people living with diabetes prefer an insulin inhaler to multiple daily injections, certain health issues (such as asthma) may prevent you from being able to use this method, so it’s important to talk about your options with your doctor.

Lastly, an insulin pump is a computerized medical device (roughly the size of a beeper, usually worn on a belt or in your pocket) that delivers a continuous, low (basal) dose of insulin. To attach it to your body, you use a needle to insert a cannula (a flexible plastic tube) into the fat tissue near your thighs, buttocks, abdomen, upper arms, or other areas with fatty tissue (the cannula, not the needle, is what remains in your body).

Since insulin pumps deliver continuous bolus doses of insulin throughout the day, you have to communicate with the pump (either by pushing a button on the device or by doing it wirelessly via an app on your phone) to get an extra bolus dose to manage blood sugar while eating. And while pumps can offer more flexibility and ease with insulin administration, they can also sometimes feel bulky to wear, and there may be a learning curve as you get adjusted to the device’s settings.

No matter which method you use to administer insulin, that decision is a “very personal” one, says One Drop coach, Rukiyyah, a diabetes prevention specialist and certified personal trainer (CPT) who’s certified in plant-based nutrition and lives with type 1 diabetes. “Using injections puts you more in the driver’s seat, as you’re not relying on technology to administer your insulin,” she explains. “However, you also don’t have all of the functionality of that technology, which can help you calculate your boluses or keep track of your insulin on board (insulin that’s still active in your body from previous bolus doses).”

On the flip side, continues Rukiyyah, while insulin pumps may help administer boluses in smaller amounts—giving a fraction of a unit instead of full units like syringes and pens—they can also feel “bulky” to wear, and there’s often a learning curve with figuring out the medical device’s settings.

Regardless of which method you lean toward, make sure you and your doctor talk about your options and which factors you should consider in your decision.

Navigating Common Challenges with Insulin

If you need insulin to manage your diabetes, there might be multiple barriers between you and your medication.

For instance, in recent years, rising costs of insulin have made access to the medication much more difficult, especially for those who already have low incomes or whose health insurance plans make it more difficult to obtain insulin at an affordable price. Fortunately, there are some resources that can help you get your diabetes medication at a more affordable price:

- The Association of Diabetes Care and Education Specialists’ (ADCES) Access & Affordability Resources

- The American Association of Clinical Endocrinologists’ (AACE) Prescription Affordability Resource Center

- GetInsulin.org (a website that connects people with diabetes to access and affordability options that match their circumstances)

- Partnership for Prescription Assistance (a program sponsored by pharmaceutical companies, doctors, and patient advocacy organizations to help low-income, uninsured people access free or low-cost brand-name medication)

- The National Institute of Diabetes and Digestive and Kidney Diseases (NIDDK) Financial Help for Diabetes Care

Even if you can get your hands on insulin, there can still be several challenges to overcome.

For one, insulin can be painful to administer. “Whether you’re injecting insulin or infusing it, taking insulin can be painful,” says Rukiyyah. “Depending on your injection or infusion site, you may hit a nerve that makes it sting. Plus, if you’re sensitive to bruising, you may find injection or infusion sites with bruises or painful bulges.” To avoid this type of pain, be sure to make swift, decisive movements as you stick yourself, and relax your muscles. It can also help to rotate injection sites and inject your insulin when it’s at room temperature as opposed to straight out of the fridge.

Then there’s the issue of accurately timing your insulin doses, particularly around meals. “Depending on the food, it can be difficult to match insulin timing to your meals,” says Rukiyyah, especially if you eat a variety of foods or decide to eat out. Overall, the goal is to take your insulin so that it works when the glucose from your food begins to enter your blood. “For fast-acting carbohydrates (juice, soda, candy, white bread, pretzels, etc.), for example, you may need to dose insulin in advance so that the peak of the medication (when insulin is working the strongest and may make blood sugar the lowest) matches the peak of the food (pre-bolusing),” explains Rukiyyah. But other types of food (and combinations of foods) may call for different timing, so it’s important to learn the techniques that work best for you with the help of your doctor.

Timing can also be tricky in relation to exercise, adds Rukiyyah. “If you decide to engage in physical activity with insulin in your system,” she explains, “the likelihood of hypoglycemia increases. Even going to the grocery store or walking around the mall can cause a drop in blood sugar if you didn’t account for being up and about when dosing and timing your insulin. That’s why it’s important to be aware and conscious of when you last dosed insulin and to always carry a fast-acting carbohydrate to counter any possible hypoglycemic episodes.”

For the most part, navigating these challenges will entail patience, education, and communication—lots of it. “When you’re just starting insulin therapy, you can expect frequent adjustments in the dosing until you and your doctor find what works best for you,” says Alex. “It’s critical to have those very clear instructions from your doctor on how much insulin to take and when, and what to do when unexpected events come up (sick days, accidentally skipping a dose or injection, etc.).” She recommends writing the instructions down so they’re easier to remember and keeping notes along the way as your regimen changes.

“Meeting with a CDCES (such as your One Drop coach), your primary care doctor, or an endocrinologist and showing them your insulin injection technique (if you’ve never done so) can also be very helpful,” she adds. “Some pharmacists are skilled in injection techniques as well, so they may be able to assist you in ensuring you’re administering your insulin correctly and most effectively, too.”

Whatever challenges you may encounter, “never hesitate to reach out to someone on your healthcare team if you have questions or are unsure of what to do,” says Alex. “Your doctor, nurse, and One Drop coach are all people who can help you answer important questions.”

This article has been clinically reviewed by Jamillah Hoy-Rosas, MPH, RDN, CDCES, and VP of clinical operations and program design at One Drop and Lisa Goldoor, RN, BSN, CDCES, clinical health coach, and pod manager at One Drop.