The path to treating and managing diabetes—a condition that impacts the health of tens of millions of people in the U.S. alone—can often be difficult to navigate, from the lifestyle changes it requires to the newfound stress it can cause. Having a sense of agency while learning how to treat diabetes is crucial; your doctor may be the one to screen, diagnose, and prescribe you what you need to take care of yourself, but living with diabetes means it’s up to you to make dozens of day-to-day decisions about your health.

The Emotional Toll of Diabetes, Regardless of Diagnosis

When you’re first told that you have diabetes—whether it’s type 1, type 2, gestational, or even prediabetes—it’s not always a given that you’ll be able to square away all of your new health needs right away, depending on your circumstances.

“The time from diagnosis to the time you’re able to meet with your medical team can range from same-day appointments to waiting a few weeks (or more) to get in with providers,” explains One Drop coach, Alexa Stelzer, a registered dietitian/nutritionist (RDN) and certified diabetes care and education specialist (CDCES).

During that time, continues Stelzer, it’s common to resort to the internet to find more details—and, inevitably, come upon conflicting information. “That can make you feel some combination of fear, confusion, frustration, shame, overwhelm, or you might even feel a powerful drive or pressure to make changes in your lifestyle,” she explains.

First, know that whatever you’re feeling, it is valid. In fact, it might help to further validate and express what you’re feeling with a therapist, particularly one who has experience working with people who are newly diagnosed with diabetes.

If you think you might benefit from speaking with a therapist, check out the ADA’s mental health provider directory, which allows you to search for a specialist based on your location.

What Happens After You’re Diagnosed with Diabetes?

“What happens immediately after a diabetes diagnosis can vary depending on a variety of factors,” says Stelzer. “The type of diabetes you’re living with, your blood sugar levels at the time of diagnosis, the symptoms you’re experiencing, and even the standard practices used by your medical care facility can all impact what happens next.”

Diagnosed with Type 1 Diabetes

Living with type 1 diabetes means your pancreas produces little or no insulin, a hormone your body needs in order to convert glucose (a.k.a. sugar) into energy. So, if you’re diagnosed with type 1 diabetes, you’ll almost always be started on insulin immediately—either in the form of insulin shots or an insulin pump (a small device that delivers insulin through a tube inserted under the skin)—and you’ll be told to start checking your blood sugar regularly, says Stelzer.

“You should be provided with immediate education on insulin administration, glucose monitoring, nutrition, potential complications, and other self-management tools,” she explains. That means working with your doctor to figure out the right type and dosage of insulin for you, any lifestyle changes you might need to make to help manage your blood sugar levels, and which method you’ll use for measuring your blood sugar: a glucose meter or a continuous glucose monitor (CGM).

“Blood sugar meters measure glucose in the bloodstream at a single point in time,” via a finger prick and test strip, explains One Drop coach, Lindsay Vettleson, RDN, CDCES, and certified personal trainer (CPT). CGMs, on the other hand, measure glucose continuously and automatically (every few minutes) via a sensor in the interstitial fluid (the fluid between cells). The CGM sensor is typically inserted into the upper arm or near your navel.

“Since blood sugar meters and CGMs measure glucose in two different areas of the body, they’ll often have different values,” notes Vettleson. “You’ll usually see the most variability in values after eating, after exercise, and after taking medications.” That said, research shows that blood sugar readings from CGMs tend to be just as accurate as readings from glucose meters. Still, it never hurts to double-check CGM data with a glucose meter to get the full picture of your health, including real-time data about your blood sugar, and predictions and insights about what you can do to maintain your health.

In addition to monitoring blood sugar, it’s important to know how to test for ketones when living with type 1 diabetes, says Vettleson. According to the American Diabetes Association (ADA), when your cells don’t get the glucose they need, your body begins to burn fat for energy instead. That fat-burning process produces acidic chemicals called ketones, and high ketone levels can potentially lead to diabetic ketoacidosis (DKA), a serious complication that, if left untreated, can lead to hypoglycemia (a.k.a. low blood sugar), hypokalemia (low potassium, which can impair your heart, muscles, and nerves), or even brain swelling, which can be fatal.

Generally speaking, it’s usually recommended to check for ketones about every four to six hours with any blood sugar reading above 240 mg/dl, when you’re sick with a cold or flu, or when you miss an insulin dose, according to the ADA. You can check for ketones with a urine test and test strip, but be sure to talk to your doctor about individual specifics on when and how to monitor your ketones, plus what to do if you find high levels of ketones in your urine.

Lastly, it’s key to establish a team of specialists beyond your primary care doctor to help you manage your condition. Although your doctor may or may not immediately refer you, Stelzer recommends finding an RDN (registered dietitian nutritionist) and CDCES (certified diabetes care and education specialist) to help you set goals and guide you in what to eat (and when) to manage your blood sugar levels with type 1 diabetes. While an RDN can help you develop strategies and plans for addressing challenges and needs related to food, a CDCES can help you learn general self-management skills and establish behavioral and treatment goals that put your self-care first.

Vettleson also recommends that you consider seeing an endocrinologist when you’re new to living with type 1 diabetes, as they can help you learn about the latest research and treatment options, not to mention work with your RDN and CDCES to establish a well-rounded self-care plan for you.

RDNs and endocrinologists are typically covered under Medicare Part B for folks living with type 1 diabetes, but if you have private insurance through your employer, you’ll have to check your insurance plan for specifics on what’s covered and what isn’t. Medicare and most private health insurance plans also usually cover visits with a CDCES, as long as they come from an accredited diabetes education program, according to the Association of Diabetes Care and Education Specialists (ADCES).

Talk to your primary care doctor about getting referrals for these specialists, or use online resources from organizations such as the Certification Board for Diabetes Care and Education (CBDCE) and the Academy of Nutrition and Dietetics to find a qualified provider near you. (In case you don’t know, many of our One Drop coaches have not only RDN and CDCES certifications, but also personal training and even nursing backgrounds. Become a One Drop Premium member to connect with a coach and learn how to lower blood sugar with a strategy that works for you.)

Diagnosed with Type 2 Diabetes

Unlike type 1 diabetes, living with type 2 diabetes typically means your pancreas does produce insulin, but it isn’t effective enough because your blood sugar levels are too high due to factors like lack of exercise or poor nutrition. All that excess glucose in the blood can cause insulin resistance, which reduces your body's ability to respond to your pancreas' production of insulin and absorb and use blood sugar for energy.

That means managing type 2 diabetes mainly focuses on certain lifestyle changes, such as following a healthier diet, getting enough movement throughout the day, managing your weight, and, if you smoke, quitting, explains Stelzer.

Sometimes your doctor will also prescribe metformin—a medication that makes it easier for insulin to move sugar out of the blood and into cells—to help manage type 2 diabetes, particularly if your high blood sugar levels don’t seem to respond to lifestyle changes alone. “If you’re living with type 2 diabetes and have very high blood sugars, you might also be started on insulin or other medications,” adds Stelzer.

As with type 1 diabetes, glucose meters and CGMs can be extremely helpful in tracking your blood sugar levels and learning how your behavior affects those levels, particularly if you take insulin to manage your type 2 diabetes, explains Vettleson.

However, while most forms of insurance cover glucose-monitoring tools for people with type 1 diabetes, it’s sometimes harder to get coverage for these devices if you live with type 2 diabetes, especially with private insurance plans. That said, Medicare Part B’s coverage of diabetes supplies is slightly more flexible: folks with type 2 diabetes can get coverage for CGMs, for example, as long as they’re taking three or more insulin injections per day, testing their blood sugar at least four times a day to help adjust insulin dosage, and seeing their doctor at least twice a year.

As is recommended for people living with type 1 diabetes, Stelzer suggests that people with type 2 diabetes also see an RDN and CDCES to help manage their condition. Again, private insurance varies widely from plan to plan, but Medicare Part B usually covers visits with an RDN and CDCES, provided that your fasting blood sugar meets certain criteria and your primary care doctor refers you to an accredited specialist.

“People living with prediabetes [characterized by higher-than-normal blood sugar levels, but not high enough yet to be considered type 2 diabetes] would also benefit from seeing an RDN and CDCES,” as well as implementing the same lifestyle changes recommended to people living with type 2 diabetes (weight loss, healthy eating, exercise, etc.), adds Stelzer. “But, unfortunately, insurance companies often don’t cover these types of visits for someone with prediabetes.”

Diagnosed with Gestational Diabetes

Gestational diabetes (GDM) is a type of diabetes that happens during pregnancy, a time when your body goes through hormonal changes that can cause insulin resistance. While all pregnant people experience some level of insulin resistance during late pregnancy, if the pancreas can’t make enough insulin to balance out the insulin resistance, GDM can develop.

Treating GDM looks pretty similar to other forms of diabetes: You’ll mainly focus on healthy eating, exercise, stress management, and regular blood sugar monitoring. For the latter, it’s usually recommended to start checking blood sugars at certain intervals (often four-six times per day), says Stelzer.

“Depending on blood sugars and risk factors, it’s possible that you’ll be started on insulin or another glucose-lowering medication,” she explains, though many people are able to manage GDM with diet and exercise alone. Either way, it’s worth noting that using blood sugar-lowering medication—whether for GDM or another glucose-related condition—is never a sign of “failure.” Everyone’s bodies are different, and some bodies simply need a different strategy to maintain healthy blood sugar levels.

In addition to regular visits with your primary care doctor and obstetrician, experts recommend working with a CDCES and RDN to manage gestational diabetes. Again, though, coverage for these visits will depend on your insurance plan. (Learn more about how to manage gestational diabetes here.)

Learning How to Live with Diabetes

As of now, there’s no “cure” for diabetes. Whether you have type 1 or type 2, chances are, you’ll be managing the condition for most, if not all of your life. (That said, it can be possible to have type 2 diabetes in remission, defined as having an A1C of 6.5% or lower for at least three months without the use of any glucose-lowering medications.)

Considering the chronic nature of diabetes, burnout is common in managing the condition. “Diabetes can also be unpredictable at times,” notes Vettleson. “Even if you follow the same routine day to day (healthy eating, exercise, medication, etc.), it’s likely that you’ll get different results in your blood sugar. The goal is to focus on how to cope with change and be able to handle your health management on an ongoing basis.”

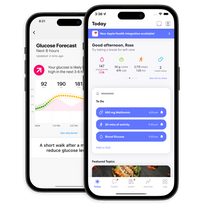

Stelzer recommends establishing a solid support system, whether you find that in friends, family, or even your diabetes care team—including your One Drop coach. Along the way, enlist their help to establish a self-care checklist, suggests Vettleson. “This can help you become more organized with diabetes-related tasks such as meal planning, exercise, taking meds, getting supplies, etc.,” she explains. (Learn how the One Drop app and One Drop Premium membership can provide these tools to keep you organized, not to mention give you the confidence and motivation you need to feel your best.)

“Find people who can relate to what you’re going through and who can help you stay positive,” adds Stelzer. “It’s totally okay to feel frustrated, fearful, or overwhelmed at times. Try to reflect on the progress you’ve already made, no matter how big or small. Celebrate your wins, even the ones that feel little, because they’re all signs of growth and contribute to a healthier you.” (Here are more ways to make your diabetes data feel less overwhelming.)

Overall, remember to set realistic goals and expectations for yourself as you learn about your health and ways to manage it. After all, treating diabetes isn’t about achieving perfection; it’s about striving to feel like the best version of yourself, whatever that looks like for you, and whatever your diabetes diagnosis.

This article has been clinically reviewed by Jamillah Hoy-Rosas, MPH, RDN, CDCES, and VP of clinical operations at One Drop.